Search results

-

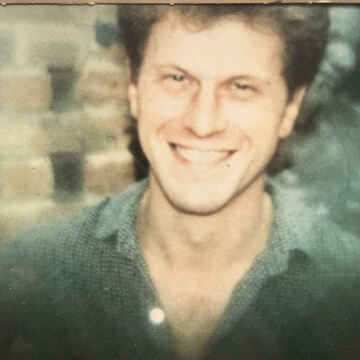

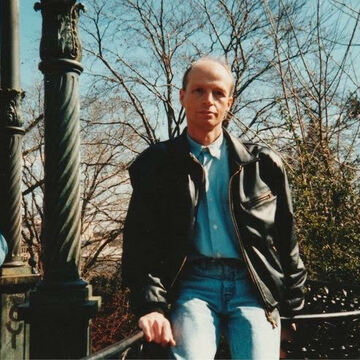

22 August 2021 Thirty years ago today my best friend the artist Clifford Haseldine died (21/12/56 - 22/08/91). We were friends for 23 years. He lived in Hackney, studied at St.Martins School of Art, moved to Stoke Newington in the seventies as a student, then Brighton in the eighties where he met his beloved partner Andrew Copus. They moved to Leicester where Clifford died. He was honest, funny, bright and far braver than he ever realised. He changed my life and I think about him every day. Words by Robert Hamberger Extract from the book ‘A Length of Road: Finding Myself in the Footsteps of John Clare’ by Robert Hamberger. One summer we took our mothers to one of his few exhibitions, in a small gallery along Brighton seafront. Mysterious underwater landscapes were displayed alongside pictures full of penises and men taking part in wanking contests. My mother laughed and hooted at the rude ones until tears ran down her face. Clifford’s mother noted in the visitors’ book that she preferred the underwater landscapes. There were years of self-doubt, when he had neither the space, the money nor the confidence to paint. Then, the year before he died, a waterfall of art poured from him again, as if it might save him: a self-portrait with a feather; an autumn cherry tree from his garden; portraits and simple charcoal nudes of Andrew, a patient model; stand-up wooden cut outs of dogs and cats and abundant flowers in vases, which he painted for money and never sold. Dozens of paintings, sketches, pen and ink drawings with water colour and chalk, which he told me were all about energy, so a cluster of images recurred in them. Cartoon-like pylons, chimney stacks, cannons, telegraph poles, Iight bulbs, gasometers, power stations and atomic mushroom clouds wrestled with river shapes swathing through each picture. Nature played a part in this energy. Suns and half-moons, seaweed, snail shells, thistles, bulrushes, lily pads and fuschias; a lightning bolt withering an orchid, and throughout these images what I assumed might be him confronting his impending death: a phoenix again and again, triumphant or maimed, a blue bird with outstretched wings.

-

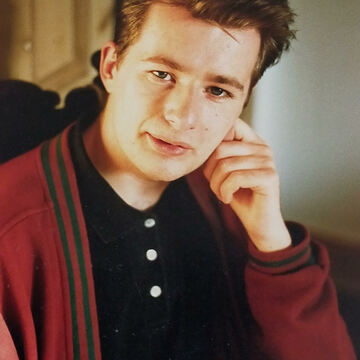

Clive Bentley 7 August 1961 - 17 August 1994 Clive’s Brighton life began at Sussex University when he started an Environmental Science degree in 1979. After this, he embarked on training as an accountant and thanks to a fascination for detail and his meticulous approach; he was set for a successful career. Testing HIV positive started Clive on a journey of personal discovery which would influence the rest of his life and everyone who knew him. At a time when fear and hostility surrounding HIV were at their most hysterical, Clive made the decision to confront his diagnosis head-on. He was deeply committed to understanding the virus and helping others do the same. Along with getting to grips with the mechanics of the disease, Clive invested huge amounts of energy exploring the personal impact of HIV on his life and others. For Clive, who co-founded Body Positive with Graham Wilkinson in 1985, and then became Sussex AIDS Centre & Helpline’s first administrator in 1986, his work was never just a job. Clive was never simply motivated by his own struggle. He was a committed socialist, enraged by all forms of inequality and discrimination. Where his brain held knowledge, his heart was always in touch with the human consequences of treating others as outsiders. Clive also had a great sense of humour and a tremendous wit which was a release from the collective pain of HIV and a way of bringing people together in the face of it. Not only was Clive a highly efficient administrator but also a skilled trainer and group worker, and when he was able, he loved to travel and experience other cultures, especially Italy and Italian food. Clive made a huge impact on the lives of those who knew him and loved him, but also on those who only met him briefly. He was a unique and special individual and those who met him were different because of the experience. It’s in that difference that we have a permanent reminder of his too brief but explosive presence among us.

-

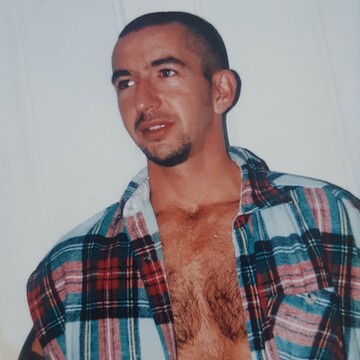

David Andrew Jones, known to everyone as Cooch, entered my life in the late summer of 1987. I was immediately taken by his dark good looks and the amazing twinkle in his Celtic blue eyes. Our relationship was tumultuous, but fun and loving in so many ways. David had his own interests and loved his freedom, so he didn’t settle into work easily, instead he dreamt of going to university to study design - his real passion. In 1994 after completing an Art Foundation course, he secured a place at Kingston University and we moved to a modernist house in Shepperton. These were happy days for us because David loved his course and I’d found my dream job, but sadly things were not to last. In 1995 we both tested HIV positive after naively assuming we’d be negative, and it wasn’t long before I fell ill with pneumonia and cytomegalovirus (CMV) - both linked to the late stages of AIDS. My stomach, eyes and lungs were also badly affected, and I remember the consultant telling me I had six months left to live, but at that time David showed no symptoms. New HIV drugs improved my health but there were hideous side effects to deal with. I needed a level of care that David was happy to give, so we sold our house and toured Europe to enjoy what we both assumed would be the last part of our lives together. David preferred a strict diet and keeping fit to any medication, but in March 1999 he started to get ill and was diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Despite advice that any treatment would be pointless, he insisted on a chemotherapy program which left him tied to opiates to help with the pain and a shadow of his former self. He was incredibly brave and still wanted to care for me, but the roles were reversed and in August David had to go into hospital. I slept on the floor by his bed so I could attend to his personal care and dignity, but he never left the ward and died there in October. A big funeral took place with all his friends and family present. David and I spent 12 years together filled with passion, love, adventure and kinky spontaneity. He was different and his own man, but kind and honest. A dare devil who remained true to his own values. Dwi'n dy garu di yn wastad ac am byth – Richard Jeneway

-

David Waghorn David was born in Andover in 1965. When we met in 1999, many of our friends were still unwell or dying despite recent improvements in Antivirals. David was well known on the scene thanks to working at the Aquarium Bar, Threshers on St James’ Street, and volunteering at Open Door where he did the cooking. Later he also volunteered at Terrence Higgins Trust and led on organising the World AIDS Day Vigil which back then took place on the Old Steine. David had also cared for his previous partner Vince who’d died from AIDS some years earlier, and he studied art at University of Brighton, although he’d have been first to admit his social life and fulfilment often came first! David’s interests were wide ranging, spanning clubs and bars, men and sex, art and reading, science fiction and Dr Who, music of all sorts (especially Bowie), excellent cookery, gardening, and his flat which was an inspiring, colourful and ornamental masterpiece. We often differed in outlook, so our relationship was rocky sometimes, but it was genuinely based on affection. We broke up after three years, but quickly became the best and closest of friends, with a trust, respect and intimacy that transcended our past. I haven’t had a more valued ‘best friend’ since. Sadly, in 2007 David was diagnosed with an advanced and aggressive cancer, common in people with HIV. Tragically, a pathway between the cancer and HIV had been missed, so I often wonder if David would have survived if that hadn’t happened. He wasn’t always confident dealing with health matters, but he rose spectacularly to the challenge presented by invasive operations, unmanageable pain, and a rapid decline in health. Despite everything being against him, he was brave, kind and still giving to others, battling on until his death just before Christmas in 2007. He was more resilient and braver in the face of adversity than I would have thought possible, and I will always remember our last kiss and precious quiet moments together before he died on the Howard 2 Ward, aged 42. David was a man of many facets, unrecognised talents, humour, and a deep appreciation and love for life. When I look at his picture taken at Pride, I feel his inspiration and happiness. Gary Pargeter

-

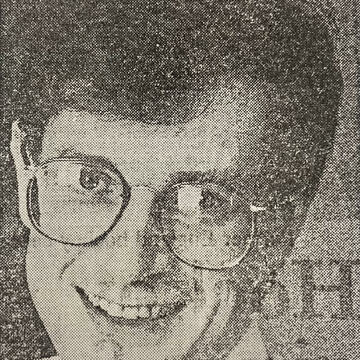

Dr Gordon McPhail was a clinical medical doctor at the Claude Nichol Clinic, when it was located in the Royal York building on the Old Steine - now a YHA hostel. He looked after patients with HIV and AIDS at the clinic between 1988 and 1990 and was quoted as saying “I jumped in at the deep end and I’m still learning about AIDS, as we all are. AIDS was thrust upon us, and we have had to learn very quickly, but I am a far better doctor now than when I started.” Dr McPhail was also a trustee of the Sussex AIDS Trust, and in 1989 he helped launch a £2.5 million appeal to build a hospice on a disused hospital site in Bevendean with the motto ‘living with AIDS, not dying with it.’ He believed the facility was vital to provide convalescent care for AIDS patients, and respite for the people looking after them. His dream was realized when the Sussex Beacon opened its doors in 1992. Gordon died of bronchial pneumonia, an AIDS related illness, at his Brighton home on 31 October 1991 aged 34. Colleagues described him as an excellent doctor and a very caring man. He was also a devout Quaker, and asked that friends and colleagues attend any service they chose after his death. A memorial meeting was held for him at the Friends Meeting House in Ship Street at 2.30pm on 10 November 1991.

-

Eddie and I met at Earls Court’s Club Copacabana on Tuesday 6 September 1983, when I accidentally tripped him up and spilt his drink. Mortified I bought him another one and we got chatting. I was a spikey haired post-punk/goth 18-year-old, and Eddie a stereotypical 1980’s clone. He invited me back to his flat in Chiswick and I stayed for 5 days, missing college. I told my parents I was staying with friends. Within a few months I left college and moved in. It was a gradual process, but Eddie knew I was serious when my record collection arrived. Eddie was born and brought up in Glasgow on the infamous Easterhouse estate. He was a proud working-class man and HGV driver who drove Adam & Ants and Jordan around Italy on their 1978 tour. Eddie tried in vain to turn me into a clone, by taking me to all the bars and leather clubs in London. It was around this time that we read about a disease largely affecting gay men in the States called GRID (Gay Related Immune Deficiency), later known as AIDS. It became all the talk in the gay press and bars. We volunteered to take part in early research conducted at Hammersmith Hospital and regularly had our bloods tested. We were together for 2 years, and remained close friends after we broke up. A few months later Eddie tested positive, and he joined the organisation Body Positive through which he found purpose, support and friendship. Pretty soon, he was the centre’s caretaker, one of the unseen heroes doing the unglamourous but much needed jobs. When Eddie became unwell, he decided not to go to the London Lighthouse, which was nearer to his home. Instead, he chose the Mildmay Mission in East London, because as a proud working-class man he felt more comfortable there. After Eddie died, I wanted to make a quilt panel for him, so I joined a quilt making workshop in Brighton run by Arthur Law. The panel I made for Eddie shows all the simple pleasures which made him happy. A mug of coffee, some hobnobs, a cigarette and the Evening Standard crossword. After completing the quilt panel, his death still felt too raw for me to show the piece in the 1993 Brighton Remembers, so I kept it at home, until now.

-

Father Marcus Riggs (1955 – 10 July 1998) When I met Father Marcus Riggs for the first time, the man dressed in full biker leathers was completely unexpected, and I immediately felt the presence of someone quite unique. Marcus wasn’t the kind of human being who just passes through life, instead he lived it to the full, and made a profound impact on those he encountered along the way. When he took up his first Brighton ministry, he lived in the basement flat of the vicarage at St. Michael’s Church. He was soon working at the First Base Day Centre for the homeless, and it was perhaps this experience that inspired him to try to establish a drop-in centre for those diagnosed with HIV in the city. In the early days, all Marcus could offer was peer support to those who needed it from his flat, so he took the decision to make his home an ‘open door.’ And as a result of his persistent lobbying, determination, and refusal to keep quiet, Marcus eventually managed to persuade the Chichester Diocese to fund a day centre in Brighton, and in 1988, Open Door was born at 35 Camelford Street in Kemptown. Despite pressure to do so, Marcus never used Open Door as an opportunity to evangelise, because he believed he’d been ‘sent as one who serves,’ and that people could see good and God in the work. Marcus had an architectural background which proved useful as 35 Camelford Street was in a poor state, with everything needing to be done from scratch in more ways than one. Running the project demanded every ounce of Marcus’s energy but from the start he was helped by a wonderful team of volunteers. Word quickly spread, and it wasn’t long before Open Door was established as the place to go for peer support, understanding, companionship, a listening ear, benefits advice, alternative therapy, and great food. Visits to Open Door always centred around the dining table, and it was this atmosphere that made it feel like home to the many who passed through its doors. When the first specialist HIV ward (6) opened at Hove General Hospital on Sackville Road in 1990, Marcus was an obvious choice for chaplaincy. It was here that he offered spiritual and emotional support to many, including my friend Andrea in his last days. Father Marcus was one of a kind, admired by many and loved by everyone. He died from AIDS illness on the 10 July 1998, and a funeral oration and requiem mass was held at St Augustine’s in Brighton. He was buried at the Bear Road cemetery. In 2009, the Chichester Diocese stopped supporting Open Door, but all was not lost. The great work established by Father Marcus continued when Gary Pargeter, who worked as a chef at Open Door, set up Lunch Positive in 2010. Today this amazing grass roots charity provides a welcoming, safe, and supportive space for people to meet, socialise, make friends, share a healthy meal, and get peer support. The services provided by Lunch Positive have continued to be accepting, non-judgemental, inclusive, and put together and provided by people with HIV for the community, so I’m sure Marcus will be smiling and happy to see his legacy so beautifully maintained.

-

First attempt at creating a Brighton Pride memorial In the mid-90s, legendary LGBT activist Arthur Law (RIP) led a campaign to have a Pride memorial set into the pavement by the Old Steine war memorial. In those days Brighton & Hove Council were not the gay friendly pink £ chasing politicos we know today, and the proposal was roundly rejected. A few of us gathered with Arthur one day to see his design for the memorial which he’d painstakingly picked out using flowers. My memory is not what it was, so if you were there too and remember the date, please get in touch.

-

Gardners Cafe opened its doors in October 1988 and quickly became a popular LGBT hangout in the North Laine. The picture shows a 'Be Good in Bed' poster from the Terrence Higgins Trust which was displayed on World AIDS Day 1990.

-

Gary Beverley Gary Beverley was my second partner and the first to die from AIDS. We met on a Saturday in April 1988 at the Bulldog where I was celebrating my 21st birthday. I can still picture it clearly and hear ‘Heaven is a place on earth’ playing, loudly! At the time, I was an aspiring clone, and Gary, 11 years older, had fully achieved clone status! I was drawn to his seductive smile, sparkling blue eyes, humour, wonderful laughter, tight fitting 501’s and perfectly polished DM’s. A five-year relationship began, and we were living together within months. Gary introduced me to new friends and experiences, and started my rapid exploration as a Gay man. It was exciting to share the Brighton Gay scene and beyond with Gary, but we also saw the fear and prejudice of HIV. Each year we lost more friends, saw more diagnosed, and then watched them quickly become seriously unwell, frail and die. Our relationship wasn’t always easy, but I never stopped loving Gary’s animated charm, and before AIDS progressed, his independent spirit. By 1992 Gary’s health had deteriorated and everyone commented on his weight loss and appearance. On a hot summer day in July, we both tested for HIV already knowing the results deep down. Gary had started showing signs of AIDS-related dementia, and the wonderful bright, vivacious, and independent man I loved quickly deteriorated with awful symptoms and eventually total loss of capacity. I’m sure others recall how distressing AIDS-related dementia was. I spent every day with Gary, right up to his death, willingly and wholeheartedly there as the awful disease rapidly progressed and diminished his mind and body. Throughout, he had occasional glimmers and signs of recognition, smiles and shared laughter, an outstretched hand for love and affection, and almost until the last moment, still cried out for me ‘my Gary.’ We were fortunate to be supported by loving close friends, Open Door, wonderful nurses & professionals, and so many others with HIV who stood with us in solidarity. I will always love Gary (tearful now) and remember the massively different time of HIV and AIDS, which for those who survived has been entirely life changing. Words by Gary Pargeter - 2021

-

I first met Gary sometime in the mid 80’s. I’m not sure where but I think it was to do with Body Positive business. He and his partner Sebastian were also engaged with The London Lighthouse in some capacity. Sebastian was very handsome and a few years younger than Gary. One afternoon I met them outside the Ladbrook Grove tube station with Rusty their new little Jack Russell cross who was gorgeous. They asked me to hold him whilst they went to use a loo and when they came out, we had a coffee somewhere nearby. They told me that Sebastian was moving to Brighton, with Gary following as soon as he could. I met them both again in Woolworths on Oxford St the day before Sebastian was moving, but I never saw Sebastian again because he died before I moved to Brighton. Gary was not a run of the mill chauffeur. He worked as one of the top drivers for the most important chauffeur service in London Victoria. He drove everyone - heads of state, celebrated film stars, rock musicians and many other world-famous people who specifically asked for him time and time again. I think he must have had some kind of intelligence background due to the importance of the people he drove, but I can’t say for certain. He was also a great dancer and lovely human being. Gary and Sebastian bought a house in Kemp Street a few doors up from the artist Gary Sollars. They were both members of the newly formed LGBT Line Dance group which I also joined later. We became a very close-knit group of friends and danced our hearts out for a couple of years. Sadly, Gary went from HIV status to full blown AIDS so I started visiting almost every day to take Rusty out for a walk. When I came into the living room Rusty would jump all over me and I’d kiss and cuddle him for a few minutes before going over to kiss and hug Gary. We walked all over Brighton, and when Gary went into The Sussex Beacon, Rusty came to live with me. We were told that Gary only had a few weeks to live and wanted to return home to die. We all helped, taking turns to look after Gary and do all the cooking, shopping and cleaning. The whole house became alive with fabulous energy. We laughed, cried, ate together, slept overnight and read to Gary until the final week when he slipped in and out of consciousness. Gary told us he didn’t want his sister to have anything to do with his death or its aftermath, and he left a letter at the Sussex Beacon saying they were not to inform her. Unfortunately, the letter was not read until it was too late. She arrived the day before he died and was furious that we were all having such a wonderful time making Gary’s last days positive and bearable. Gary had one of the best deaths I have ever witnessed until she poked her nose in. We would not let her interfere, but she wouldn’t leave Gary’s house until after the funeral. There was one problem, Rusty. I said I could not take him so said she’d build another kennel outside for him next to her other dogs. This horrified me and all the others, so I quickly changed my mind and took Rusty home with me that evening. He lived for another 4 happy years, and I still have an oil painting of him above my desk.

-

Graham Charles Wilkinson Graham Charles Wilkinson was one of small group of gay men in London who shared a vision for innovative new centres for people living with HIV in the UK. The group started to meet and talk about their ideas at the flat of Christopher Spence OBE, who’d later become director of the Lighthouse in Ladbroke Grove when it opened in 1986. Graham was acutely aware that Brighton was desperate for services to help the growing numbers affected by the epidemic, so he set to work bringing the vision to the coast. Determined and courageous, Graham decided to quit his job to found the Sussex AIDS Helpline in a ‘grotty’ little office on Brighton’s Western Road in October 1987. In the early days, the helpline was a very hands-on affair with Graham and a few friends answering all the calls, but despite its humble beginnings, it soon became essential for anyone needing good advice, compassion and the facts. By all accounts Graham was a shy man who found the constant battles, resistance and stigma of the times hard to manage against the backdrop of his own illness. Sometimes the stress of the situation would get the better of him, but before long the light would appear in his face alongside an infectious giggle that anyone who knew him will never forget. By all accounts, Graham was a loving and supportive man who could be relied on to give someone a cuddle. Graham lived on Devonshire Place in Kemptown with his partner and playwright John Roman Baker at the time. They used their flat as a centre for the fundraising and lobbying which helped Graham to realise his vision when the Sussex AIDS Centre and Helpline opened at 3 Cavendish Street in 1988. Despite his poor health Graham played a key role in shaping, influencing and establishing the HIV services in Brighton which continue today, and his tireless commitment served to directly impact and improve the quality of lives of countless people living with HIV in Brighton. Graham ended his days at the London Lighthouse on 22 August 1990 surrounded by friends. His service was held in St Peters Church with standing room only - a testimony to the love and respect that existed for him in the city. - Danny West - 2021 22 August 2021 This evening, John and I are listening to Donna Summer and remembering Graham Wilkinson who died this day 31 years ago at London Lighthouse (at the time there was no hospice for people with HIV/Aids in Brighton). He was a tireless gay rights campaigner from the 1970s onwards and then in the 1980s fought tooth and nail as co-founder and director of the Sussex Aids Centre & Helpline (now THT South). His work, spirit and achievements should not be forgotten. It was a time when gay men in particular, but also others with HIV, were collateral damage in a deeply Conservative society where sadly even within our own community we had to fight self-hatred while the government held out for a feared heterosexual epidemic which of course (thankfully) did not materialise. Graham inspired and touched the lives of so many, but to John and myself he was so much more. He was our family and is deeply missed. Words by Rod Evan & John Roman Baker

-

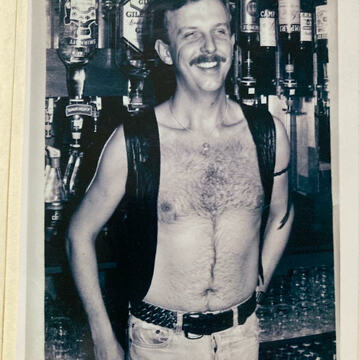

When I visited Brighton in 1986, I went to The Pink Coconut on Sunday with my mate Trevor. When the club had shut, I followed my nose to the nearest cruising spot in town and quickly became acquainted with a guy called Graham, (Bona Clone to his friends) He was everything I had fancied, big moustache, leather chaps, 501’s leather jacket, poppers and a cheeky smile. I went back with Graham and had such a great time I decided Brighton was where I would like to live. Within a week I was back staying on Trevor’s floor. On one of my nights out I went to the club called Manhattan’s where I met Graham once again. He worked there serving drinks from an alcove bar with walls covered in pictures of 80’s style clones. With a wry smile Graham told me his bar was the most popular in the club and seeing him there in just leather waistcoat and jeans, I could see why. On Graham’s invitation, I moved in with him. Our relationship burnt bright and short, but a lovely connection was made between us. I’d see Graham on the scene all the time, and one day he came over and said he’d been diagnosed HIV+. He was the first person I knew to tell me this. Back then, AIDS was still something that happened across the pond, then London and then all too quickly, Brighton. I’d not seen Graham for about six months, when I bumped into him on Brighton pier, and we had a lovely catch up. He looked great in ripped 501’s and white t-shirt, with the same smile, but then a few weeks later I heard he was in hospital with AIDS. I visited him just the once, and he was unable to speak, but I am glad I had the chance to say goodbye. What I am so pleased about is through the Brighton AIDS Memorial Project I can celebrate Graham and remind everyone of what a lovely person he was, Bona Clone a lot of the time, Bona Moan on others, but always and forever, lovely Graham.

-

HIV Hour interview which was broadcast on 13 May 2021 on Brighton local community radio, Radio Reverb.

-

You lugged it from the builder’s yard. Now it’s my turn to know its stiff weight, the slow chafe of pine against vertebrae: a decade-long kiss, flush with splinters. I closed it when I left. The lock snicked. Then I noticed it hitching a ride. It never gives up―patchy blue, invisible straps; a faint knocking though nobody’s there. So many slab hazards: repeated thumps to my skull, brass hinges clouting strangers as we creep into lifts, beds. I lie awake on its panels, framing rectangular thoughts, obsessed by the side I can't see; what grows there. The problem is you died so there’s no way to set the thing down, no wall to prop it against with its stuck handle and fracturing paint. All day we continue our back to front tango, this dance where I almost but never arrive, where I’m shut off to visitors for hours then, with one touch, swing wildly open.