An Interview with Harry Hillery

25th November 2024

“We can choose to do beautiful things – it doesn’t have to be miserable.”

I spoke with Harry Hillery, founder of the Brighton AIDS Memorial project, about his life in Brighton, remembering people with joy, and finding hope during difficult times.

This interview took place at the end of October.

I’m reading over my questions when Harry joins our video call. He’s sitting in his office at home with full bookshelves against the wall behind him, and a collection of posters and photos on the other. After we exchange pleasantries, he tells me about the walk he’d just returned from with his dogs, Boris, and Polo; rescued pugs who, Harry explains, are enjoying the outside as much as he is - when it isn’t raining.

DH: Thank you so much for chatting with me today! To start with, introduce yourself in whatever words you’d like. How would you define yourself?

HH: Well, I think a good way to start is by saying that I’m a friendly old queer bear living on the south coast with my husband and two dogs. I’m a wannabe writer and an archivist. I don’t want to define myself with a job title because the jobs we do for a living don’t usually represent us fully. I work for Lewes District Council helping their tenants have some influence and hopefully to challenge the status quo. I’m driven by a need to care for people, helping them at different times of their lives and in different situations, but I’d also like to be regarded as a writer someday. I studied creative writing at the University of Brighton and have a few projects on the go. I really enjoy writing to unearth queer perspectives on things. But yes, I’m a friendly old queer bear.

DH: I really agree with the idea of not defining yourself just by a job title. And I love the description - a friendly old queer bear on the coast. You clearly feel an attachment to Brighton and its surrounding area.

HH: It’s something that’s developed over time, especially now that I'm a dog person. I always imagined myself being a crazy old cat man, but dogs have won me over nowadays. Going out for long walks with them, no matter the weather, has enabled me to connect better with nature. I love listening to birdsong and identifying them. I saw a Jay today for the first time in a long time! Normally I see lots of other Corvids like Crows, Jackdaws and Magpies, so seeing the Jay was a pleasant surprise. I’ve also started getting into a bit of foraging, berries, and the like. It’s nice finding more ways to connect with the world around us.

DH: I personally love the wild garlic season - still a few months off. Could you share a bit of an overview of your time in Brighton?

HH: I’ll give it a go! I arrived in Brighton in the late 1980s, with a plan to prise myself out of the closet. I was in my late 20s, and I needed a safer space to discover myself. I promised that I would be honest and not hide anymore. It was a period of my life where I focused on reinvention, a complex mix of being open about my sexuality, whilst also being immersed in the horrors of the 1980s - Section 28, Thatcher, the awful media, queer bashing. It was a time of dark and light shades, ups and downs.

I’d come to Brighton from London, where the impact of AIDS was everywhere but perhaps easier to handle because it felt more diluted. London was so vast, that I didn’t feel like I was reminded about it every day. Moving to Brighton felt different, it felt more visible here. The community was more compact, so HIV / AIDS felt more present. I’m thinking about St. James’s Street, how you’d walk down it and see people, or not see people. Sometimes people would disappear, and there’d be an unspoken understanding about what was going on.

A gathering in Queen’s Park after a Pride march, c. early 90s.

The community really came together in Brighton in a way I hadn’t seen before or since really, although there’s been heartwarming solidarity around the attacks on the Trans nation. It’s really feeling like the community I remember from the 80s. Factions overcoming the past to become something big and cohesive - the knowledge that we’re all under threat, and the need to help each other out. People are generally good, and can always make good choices, acts of kindness - what’s that Harvey Milk quote about hope?

“Hope will never be silent. Burst down those closet doors once and for all and stand up and start to fight. I know you can't live on hope alone; but without hope, life is not worth living. So you, and you and you: you got to give them hope; you got to give them hope.”

We can choose to do beautiful things - it doesn’t have to be miserable. It’s the community I remember best. I became involved in the Sussex AIDS Centre and Helpline as a volunteer and got to know people and got known in return. People heard about the cafe I ran and soon it became a queer hang-out with the whole scene visiting. A play by John Roman called Crying Celibate Tears was presented at the Sussex AIDS Centre, and they used furniture from the café as props – it was such an honour!

Brighton has been my home for decades now, apart from a year in San Francisco. I have fallen in love here a few times and made a home. These days I love spending my time growing vegetables, making jam, reading, and walking the dogs. I’m a few miles east of Brighton but I feel just as connected now as I did then. I’ve realised there are very few things that matter in the grand scheme of things: people that love you, a full larder, somewhere comfortable to sleep, books, music, art…

There’s a cemetery in Paris called Père-Lachaise that’s frequently visited by the queer community because people like Oscar Wilde are buried there. There are many grand mausoleums built for rich industrialists or the like who are long forgotten, but amongst them are smaller well-tended graves with flowers, tokens and trinkets placed carefully about. The resting place of an impressionist painter maybe or a writer, but the point is they’re still remembered. It makes you realise that it’s music, art, writing and love that stays behind and leaves something beautiful in the world. No one really cares about the rich industrialist. We should all try to leave love and beauty behind us - something we can be proud of. As Derek Jarman once said, “love is life that lasts forever.”

Harry and his husband Toni on a trip to Barcelona for their honeymoon, c. 2015

DH: That was a lovely note to close on. You spoke a lot of the community that you’ve been part of in Brighton; it feels like those acts of care and solidarity are a beautiful thing to be remembered for. To you, what makes queer heritage (and remembering our collective history) important?

HH: It’s easy to forget things and become complacent. Take Pride: there’s a complicated relationship there because lots of people celebrating would have been unthinkable at one time. At the same time, those early Pride memories are at odds with what it’s become. The political messages, the camaraderie at the heart of the community, the solidarity between everyone - it isn’t there so much in the official Pride. We always need to remember how tenuous our rights are. We’re living through dark times again and I fear for my American friends, and also the Trans community. I think there’s definitely a need for more community solidarity - like a reboot of the 1980s and 1990s.

I’ve seen Brighton’s attitude to the community shift over the years. In the mid-1990s I helped set up a Lesbian and Gay Council tenant group with some colleagues. This attracted some interest, so we decided to promote it more widely. We made a logo - a small cartoon house with a pink triangle for a roof - and had leaflets printed to send out with a Council rent card mail-out to 11,000 homes.

At the very last minute the Leader of the Council found out and we had to remove every leaflet from thousands of envelopes. Brighton now takes every opportunity to promote itself as a gay capital, but then they wanted to distance themselves from this, HIV and AIDS as they saw it as ‘off-putting.’ It’s important to remember how quickly things can change and remember our history because it’s relevant to any future. We need to remember how, as a community, we reacted to HIV and AIDS in case we need to do so again. The government will continue to give and take our rights away, so we need to be aware of how we fought before so we can be ready to fight for our rights again and again.

DH: There’s something really powerful about memory being related to solidarity and community. But, as you’ve touched on, there’s also a lot of grief and pain in our community heritage. How can we find joy alongside this? Should we?

HH: I think we should celebrate people; that’s the focus of the Brighton AIDS Memorial project I created on Instagram and the Queer Heritage South website. When I went to AIDS memorial events, there were names I didn’t recognise, but others that punched through with emotions and memories. I was left wondering, who knows their stories? I believe sharing the stories of people who’ve died helps them to live on, existing beyond sometimes tragically short lives. There are also many heroes of the AIDS epidemic that should be remembered for their courage, work, and care. I personally didn’t want my friend Andrea to be remembered just as someone who had AIDS, I wanted the flamboyant, funny, vial of Brazilian sunshine to be remembered too. Illness and death shouldn’t define people who were lost to AIDS. Sharing their stories bucks that definition and instead we remember the bright flames they were, and the reasons why we loved them.

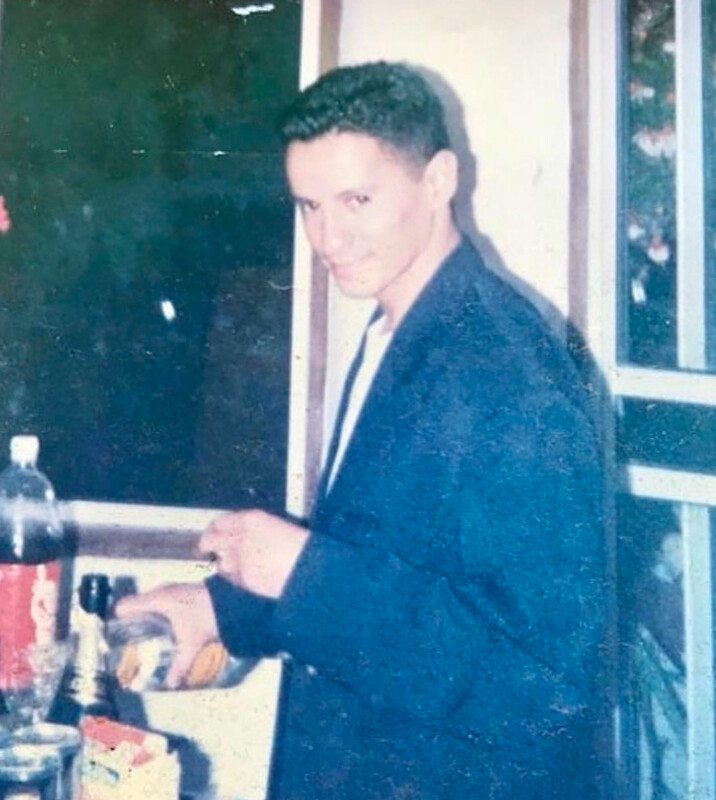

Harry’s friend Andrea who died of AIDS in 1991. He inspired the Brighton AIDS Memorial

DH: The Memorial Project has been crucial to holding up that idea of celebrating people and their stories. Out of everything that’s come of the project, what is the thing you’re proudest of?

HH: I honestly think I’m proudest of the cafe I ran in the late 80s & early 90s. It’s the period of my life when I felt really fulfilled and happy despite the backdrop of Thatcher, Section 28 & HIV/AIDS. I was out for the first time, and I created something that organically became the queer hangout of the city. A safe place for others to express themselves. It became a delicious dish of diversity and felt natural and lovely - like it could be the future. The atmosphere of the café was about openness and acceptance – an alternative for free thinking people, gay or straight.

There’s another memory that makes me proud. I knew a lovely man called Kevin Dodd who chaired the Body Positive Group at the Sussex AIDS Centre. We had a good friendship, so when I started the Brighton AIDS Memorial he was one of the first people I thought about remembering. In 2021 I held an exhibition with the help of Lunch Positive with panels made for people like Kevin. I’d met a woman called Ruth at another event who I’d asked to consider contributing a story, and she came down to have a look. I saw her standing in front of Kevin’s photograph for ages, so I went over. ‘That’s Kevin,’ she said. ‘He was my brother.’ She hadn’t realised that I’d known Kevin or that he would be in the exhibition. She was clearly moved by him being there and glad to see him remembered. She returned later with the original order of service I’d talked about in my story – it was a beautiful moment & made me realise how important remembrance like this is. People have found contributing cathartic and think it’s beautiful that so many people are remembered and loved all these years later.

DH: That’s a lovely memory. I think the Brighton AIDS Memorial has done a great job building trust with the community to handle these memories with care. How should organisations and projects like ours build trust too?

HH: Gaining trust can be a slow burner. With the Brighton AIDS Memorial, I knew it would be raw and sensitive to some. Many people tuck painful memories away and don’t want to revisit them. It's important to respect this and not push people to share things, but instead give them the opportunity to do so when they feel comfortable. When I started the project I tried to introduce it gently with the help of trusted organisations like Lunch Positive.

With projects like Queer Heritage South, trust can be built on the basis of its permanence. It’s a safe place for memories and artefacts to be recorded and preserved. Projects in Brighton have come and gone and there are questions about who might have something, or where items have ended up.

There was a man called Arthur Law. He was a strong-willed activist and also a skilled embroiderer. He made many banners and panels for groups in the 1980s and 1990s. The most beautiful thing he made was a huge sewn quilt with 134 stars representing all those lost to AIDS at that point in time – 1993. Where is it now? No one seems to know.

Having responsibility and transparency is necessary for heritage and memorial projects to gain trust from the community so artefacts like these are found, cared for, and displayed once more. It’s important to collect stories, ephemera, and objects before they disappear. Sometimes the material stuff is thrown away, so projects like the Brighton AIDS Memorial and Queer Heritage South can be places for the stories to live on.

Harry in San Francisco in October this year. He is handing over a new quilt he had made for Andrea, which is now part of NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt.