Simon Dwyer

- Title

- Simon Dwyer

- Date

- 1997

- Contributor

- Harry Hillery

- Format

- jpg

- Type

- jpg

- Creator

- Fiona Dwyer

- Language

- English

- Rights

- Attribution - Non Commercial - Share Alike 4.0 International License

Description:

Simon Mckenzie Dwyer was a curious fellow. A pub brawler and a football hooligan. A Plymouth Argyle supporter with a tender soul and ferocious intellect. Raised a Catholic, abused and beaten by Christian brothers, he grew up feeling anger, guilt and shame but found David Bowie and a way out.

I first met him when I was 17 and an understudy at Chichester Festival Theatre. I had just bought a red dress and he was stage crew watching the rehearsals. He saw me and said “I’m going to marry that girl in red.”

I grew up in a small village in West Sussex, sheltered and naïve. I followed him to a squat in an enormous council estate in Poplar, East London. He started a fanzine in the late 70s called ‘Rapid Eye Movement’ and I was introduced to his friends who were musicians, writers, poets, performance artists and one glorious heroin addicted painter called Nicky Slagg who lived in the underbelly of a derelict Wapping warehouse.

I remember stapling the fanzine pages together. The music magazine Sounds picked up on Simon’s interview with Crass who had refused interviews with the mainstream press. Like so many others, Crass co-founder Penny Rimbaud respected Simon and agreed that Sounds could re-print the article. Sounds then employed Simon as a music journalist. Much to my excitement he reported on Adam and the Ants and all the punk bands. He also went on a Belgium tour with The Cure, but his passion was for sub culture and his own philosophies on life and increasingly death.

He poured his heartfelt ideas into his own Rapid Eye project and always ahead of the game he began to amass a following, some less savoury than others. Years after his death I found a letter that was postmarked Waco, Texas – a rambling missive from David Koresh.

In the late 80s he started to feel unwell, lost weight and developed strange rashes. He took a HIV test in a private hidden clinic in London. The results were ‘unequivocal’ and we knew what that meant. He was officially diagnosed in 1992 and placed in the wonderful care of Dr Martin Fisher. He continued with Rapid Eye and writing for different projects with Genesis P-Orridge. Gen had been a dear friend for many years and felt the loss of Simon very deeply. Derek Jarman and Gilbert and George also supported him when his health began to deteriorate.

Simon had several admissions to the rather grim Ward 6 in Hove (now a block of luxury flats – I wonder if the owners know the history). He was pumped full of toxic agents that were well intentioned and supposedly maintaining his CD4 count and reducing the viral load, but they had horrendous side effects. He had one drug that induced psychotic episodes during which he’d ask me to leave the house and hide the knives because he feared he might “butcher the cats.” At this point, for my safety, he was admitted to the amazingly beautiful Sussex Beacon where he decided to stop taking the drugs. He spent the last six months of his life there. The staff there were angels, always loving and kind.

Simon used to smoke at least 40 Dunhill International a day and made so many burn holes in his bedding that they had a special rotating set of sheets and duvet covers for him. He fell into a loving, cherished morphine induced slumber. The last time he woke up, he asked me for a fag which I held to his lips. He savoured two drags and then slept gracefully. A few days later he died in my arms, clean and fresh and sweet as a daisy. When the doctor, Jonathan Wastie, came in to certify the death he kissed Simon on the forehead and said “farewell darling.” I said “sail safe dearest with Peter our son who was born sleeping in this world but reaching out to embrace you in the next.” Words by Fiona Dwyer

Obituary written by Paul Cecil for The Independent – published 28 October 1997.

Simon McKenzie Dwyer, writer and editor: born Salisbury, Rhodesia 28 November 1959; married 1982 Fiona Pritchard (one son deceased); died Brighton, East Sussex 26 September 1997.

Simon was an extraordinary young man who established himself as one of the leading commentators and contributors to, the artistic and creative subculture of the last two decades. A writer first and foremost, he focused his work through the magazine he first conceived in 1979 and named Rapid Eye. The youngest of three sons, Dwyer was born in Salisbury, Rhodesia, in 1959 but moved to England a year later, when his family returned, moving around the country before settling in Plymouth, where Dwyer attended, somewhat reluctantly, the local schools. He left Tavistock Comprehensive shortly after his 16th birthday. This was the time of punk which turned many heads away from convention and towards the exploration of the alternative and improbable. It was precisely into this area of burgeoning cultural expansion that Dwyer focused his energies. His understanding of the possibilities awakened by rejecting hierarchical and formal society was already gestating, as was his willingness to embrace the art and performance of transgression. In 1978 he moved to London and began, in the tradition of punk writers, developing his own fanzine, Rapid Eye. The first issue which hit the streets in 1979, included a feature article on anarchist band Crass which was quickly picked up by the music paper Sounds. Dwyer established himself rapidly as a regular contributor to Sounds, interviewing the famous, the soon to be famous, and – as is inevitable in an industry that so vicariously promotes and demotes – the once famous and the never will be famous. This eclectic mix served mainly to reinforce in Dwyer the belief that status is the least relevant concerns and that it is the human level, and creative integrity, that above all marks out the true artist.

By 1982 Dwyer had moved to Brighton, and it was in that year that he married Fiona Pritchard. It was soon after this that sadness struck their lives, with the death at birth of their only child, Peter. The world of commercial journalism became ever less attractive to Dwyer and he moved from it to that of interior design, joining Rhodec International. Alongside this work, he continued writing, developing Rapid Eye into an increasingly lavish exemplar of fanzine art. Indeed, the famous “Black” edition which he produced in 1986 has since become a sought-after collector’s item. However Rapid Eye as a concept, despite its plaudits, had for him never reached its potential. Calling in favours from friends and contacts he had made through his earlier work, he set out to produce the ‘zine to end all ‘zines: a coffee table edition, massive in scope, scale and vision. And how those favours rolled in: Andy Warhol provided the frontispiece; William Burroughs sent three pieces of writing, “And His Name was Rover”, “The Johnson Family” and the “Fall of Art”. Kathy Acker, Genesis P-Orridge and Colin Wilson also contributed to the volume, as did Derek Jarman. Alongside this galaxy of stars, Dwyer included, with no less care or column inches, a raft of unknown writers with specialisms ranging from conspiracy theories to foot-binding. Over a year in the making, Rapid Eye 1 (1989) proved to be inspirational, in the words of the New Musical Express “a veritable treasure-trove of mind-activating information. Penetrating, comprehensive, most illuminating.” With the task of the first “real” issue behind him, Dwyer and his wife transported their life to America. They were there to develop Rhodec’s North American presence, but inevitably spent the best part of their year travelling across country. It was this, certainly, that provided the inspiration for Dwyer’s greatest exploration of his journalistic skill, a text of 100,00 words, “The Plague Yard: Altered States of America”. It was on their return to England in 1991 that Dwyer learned that he was HIV positive. While coming to terms with the diagnosis he completed “Plague Yard” and concluded a commercial deal with Creation Books for Rapid Eye. The idea of publishing “Plague Yard” as a book was floated. Those who read the text found it astonishing: the art of the travel writer re-configured into a plea for cultural freedom, with the punk aesthetic not only intact, but validated as never before. Focusing as much on low art as high, the piece shows Dwyer to be much at home with the disposed idealist as with the art-elite glitterati. But Dwyer for all the praise heaped on him, remained true to the spirit that had long driven him, and declined the offers. “Plague Yard” was not to be used to announce his elevation in the literary field, instead it was to exist, and stand or fall on its merits, alongside many other pieces, simply as a contribution to Rapid Eye 2.

By 1993 the debilitating effects of HIV were becoming an unavoidable presence in his life. Minor ailments mounted up, fatigue set in, and work began on the third and final volume of Rapid Eye. The centrepiece of the volume is a startling piece, by Dwyer himself, on the art of Gilbert and George who offered the use of their painting “We” as the cover. Rapid Eye 3 was launched in London in 1994.

I first met him when I was 17 and an understudy at Chichester Festival Theatre. I had just bought a red dress and he was stage crew watching the rehearsals. He saw me and said “I’m going to marry that girl in red.”

I grew up in a small village in West Sussex, sheltered and naïve. I followed him to a squat in an enormous council estate in Poplar, East London. He started a fanzine in the late 70s called ‘Rapid Eye Movement’ and I was introduced to his friends who were musicians, writers, poets, performance artists and one glorious heroin addicted painter called Nicky Slagg who lived in the underbelly of a derelict Wapping warehouse.

I remember stapling the fanzine pages together. The music magazine Sounds picked up on Simon’s interview with Crass who had refused interviews with the mainstream press. Like so many others, Crass co-founder Penny Rimbaud respected Simon and agreed that Sounds could re-print the article. Sounds then employed Simon as a music journalist. Much to my excitement he reported on Adam and the Ants and all the punk bands. He also went on a Belgium tour with The Cure, but his passion was for sub culture and his own philosophies on life and increasingly death.

He poured his heartfelt ideas into his own Rapid Eye project and always ahead of the game he began to amass a following, some less savoury than others. Years after his death I found a letter that was postmarked Waco, Texas – a rambling missive from David Koresh.

In the late 80s he started to feel unwell, lost weight and developed strange rashes. He took a HIV test in a private hidden clinic in London. The results were ‘unequivocal’ and we knew what that meant. He was officially diagnosed in 1992 and placed in the wonderful care of Dr Martin Fisher. He continued with Rapid Eye and writing for different projects with Genesis P-Orridge. Gen had been a dear friend for many years and felt the loss of Simon very deeply. Derek Jarman and Gilbert and George also supported him when his health began to deteriorate.

Simon had several admissions to the rather grim Ward 6 in Hove (now a block of luxury flats – I wonder if the owners know the history). He was pumped full of toxic agents that were well intentioned and supposedly maintaining his CD4 count and reducing the viral load, but they had horrendous side effects. He had one drug that induced psychotic episodes during which he’d ask me to leave the house and hide the knives because he feared he might “butcher the cats.” At this point, for my safety, he was admitted to the amazingly beautiful Sussex Beacon where he decided to stop taking the drugs. He spent the last six months of his life there. The staff there were angels, always loving and kind.

Simon used to smoke at least 40 Dunhill International a day and made so many burn holes in his bedding that they had a special rotating set of sheets and duvet covers for him. He fell into a loving, cherished morphine induced slumber. The last time he woke up, he asked me for a fag which I held to his lips. He savoured two drags and then slept gracefully. A few days later he died in my arms, clean and fresh and sweet as a daisy. When the doctor, Jonathan Wastie, came in to certify the death he kissed Simon on the forehead and said “farewell darling.” I said “sail safe dearest with Peter our son who was born sleeping in this world but reaching out to embrace you in the next.” Words by Fiona Dwyer

Obituary written by Paul Cecil for The Independent – published 28 October 1997.

Simon McKenzie Dwyer, writer and editor: born Salisbury, Rhodesia 28 November 1959; married 1982 Fiona Pritchard (one son deceased); died Brighton, East Sussex 26 September 1997.

Simon was an extraordinary young man who established himself as one of the leading commentators and contributors to, the artistic and creative subculture of the last two decades. A writer first and foremost, he focused his work through the magazine he first conceived in 1979 and named Rapid Eye. The youngest of three sons, Dwyer was born in Salisbury, Rhodesia, in 1959 but moved to England a year later, when his family returned, moving around the country before settling in Plymouth, where Dwyer attended, somewhat reluctantly, the local schools. He left Tavistock Comprehensive shortly after his 16th birthday. This was the time of punk which turned many heads away from convention and towards the exploration of the alternative and improbable. It was precisely into this area of burgeoning cultural expansion that Dwyer focused his energies. His understanding of the possibilities awakened by rejecting hierarchical and formal society was already gestating, as was his willingness to embrace the art and performance of transgression. In 1978 he moved to London and began, in the tradition of punk writers, developing his own fanzine, Rapid Eye. The first issue which hit the streets in 1979, included a feature article on anarchist band Crass which was quickly picked up by the music paper Sounds. Dwyer established himself rapidly as a regular contributor to Sounds, interviewing the famous, the soon to be famous, and – as is inevitable in an industry that so vicariously promotes and demotes – the once famous and the never will be famous. This eclectic mix served mainly to reinforce in Dwyer the belief that status is the least relevant concerns and that it is the human level, and creative integrity, that above all marks out the true artist.

By 1982 Dwyer had moved to Brighton, and it was in that year that he married Fiona Pritchard. It was soon after this that sadness struck their lives, with the death at birth of their only child, Peter. The world of commercial journalism became ever less attractive to Dwyer and he moved from it to that of interior design, joining Rhodec International. Alongside this work, he continued writing, developing Rapid Eye into an increasingly lavish exemplar of fanzine art. Indeed, the famous “Black” edition which he produced in 1986 has since become a sought-after collector’s item. However Rapid Eye as a concept, despite its plaudits, had for him never reached its potential. Calling in favours from friends and contacts he had made through his earlier work, he set out to produce the ‘zine to end all ‘zines: a coffee table edition, massive in scope, scale and vision. And how those favours rolled in: Andy Warhol provided the frontispiece; William Burroughs sent three pieces of writing, “And His Name was Rover”, “The Johnson Family” and the “Fall of Art”. Kathy Acker, Genesis P-Orridge and Colin Wilson also contributed to the volume, as did Derek Jarman. Alongside this galaxy of stars, Dwyer included, with no less care or column inches, a raft of unknown writers with specialisms ranging from conspiracy theories to foot-binding. Over a year in the making, Rapid Eye 1 (1989) proved to be inspirational, in the words of the New Musical Express “a veritable treasure-trove of mind-activating information. Penetrating, comprehensive, most illuminating.” With the task of the first “real” issue behind him, Dwyer and his wife transported their life to America. They were there to develop Rhodec’s North American presence, but inevitably spent the best part of their year travelling across country. It was this, certainly, that provided the inspiration for Dwyer’s greatest exploration of his journalistic skill, a text of 100,00 words, “The Plague Yard: Altered States of America”. It was on their return to England in 1991 that Dwyer learned that he was HIV positive. While coming to terms with the diagnosis he completed “Plague Yard” and concluded a commercial deal with Creation Books for Rapid Eye. The idea of publishing “Plague Yard” as a book was floated. Those who read the text found it astonishing: the art of the travel writer re-configured into a plea for cultural freedom, with the punk aesthetic not only intact, but validated as never before. Focusing as much on low art as high, the piece shows Dwyer to be much at home with the disposed idealist as with the art-elite glitterati. But Dwyer for all the praise heaped on him, remained true to the spirit that had long driven him, and declined the offers. “Plague Yard” was not to be used to announce his elevation in the literary field, instead it was to exist, and stand or fall on its merits, alongside many other pieces, simply as a contribution to Rapid Eye 2.

By 1993 the debilitating effects of HIV were becoming an unavoidable presence in his life. Minor ailments mounted up, fatigue set in, and work began on the third and final volume of Rapid Eye. The centrepiece of the volume is a startling piece, by Dwyer himself, on the art of Gilbert and George who offered the use of their painting “We” as the cover. Rapid Eye 3 was launched in London in 1994.

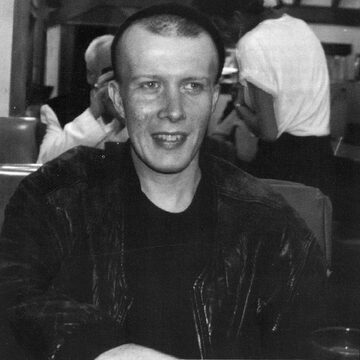

Simon Dwyer

Simon Dwyer

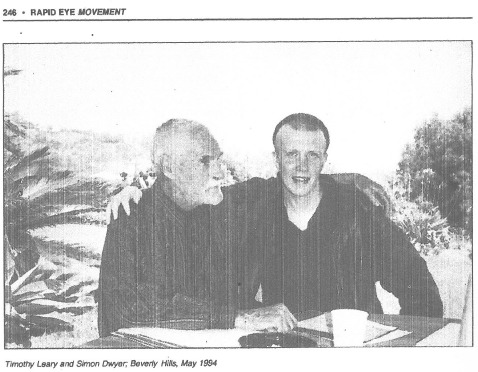

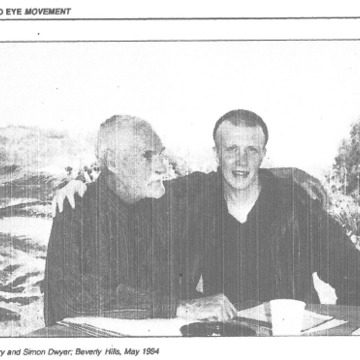

Simon with Timothy Leary - Beverly Hills - May 1994

Simon with Timothy Leary - Beverly Hills - May 1994

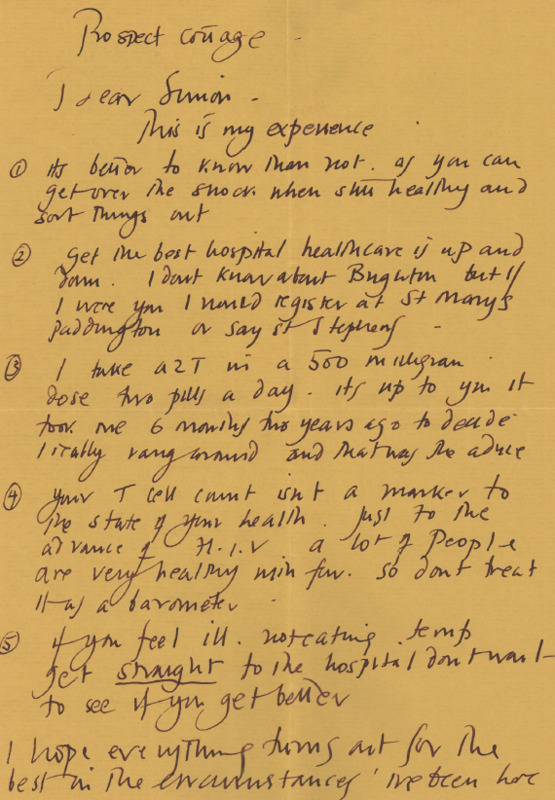

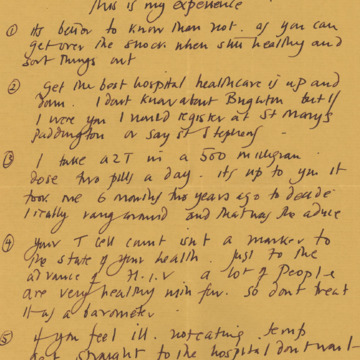

Letter to Simon from Derek Jarman

Letter to Simon from Derek Jarman

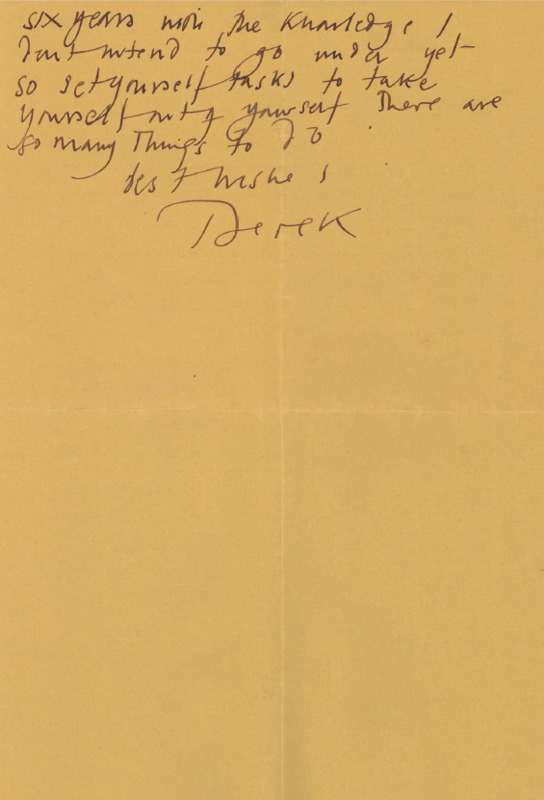

Letter to Simon from Derek Jarman (continued)

Letter to Simon from Derek Jarman (continued)

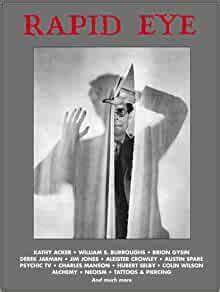

Dwyer: the 'zine to end all 'zines

Dwyer: the 'zine to end all 'zines

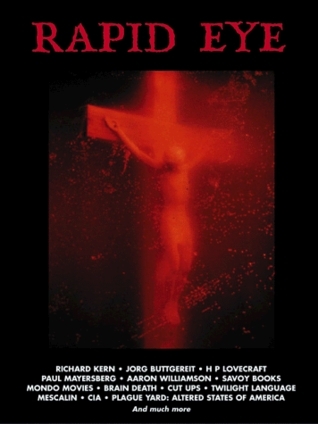

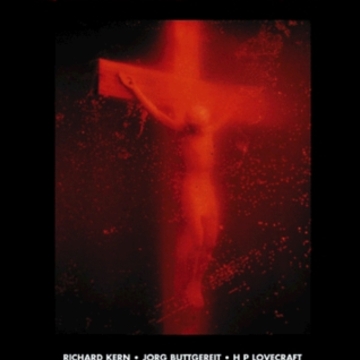

Rapid Eye 1

Rapid Eye 1

Rapid Eye 2

Rapid Eye 2

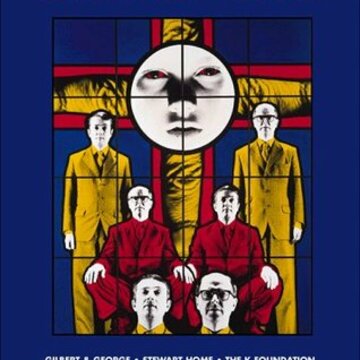

Rapid Eye 3

Rapid Eye 3